Late afternoon fence line, Brush Creek Ranch, Wyoming. Photo by Dawn Chandler

When I was a teenager there were two places at home where I liked to do my homework. If I really needed to concentrate — say when writing a paper — I would work at my little desk in my tiny bedroom. At the end of a narrow-book-lined corridor upstairs, it was about as isolated as I could get from my family.

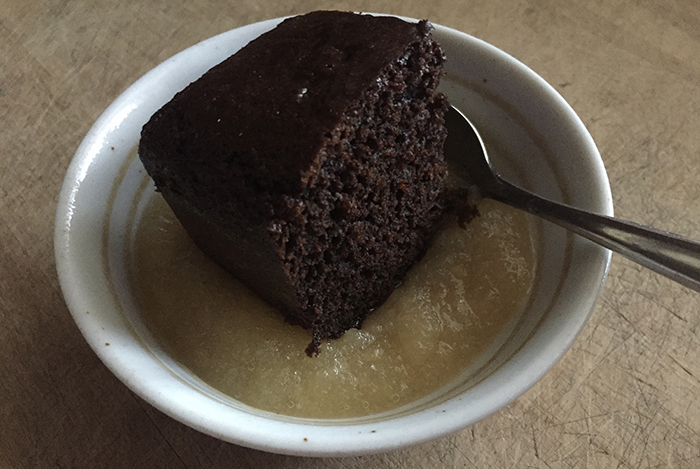

But mostly my favorite place to study was in the downstairs front hall. The hub of the ground floor, it was just a few yards away from the kitchen, where in the late afternoons my mother would be found cooking supper, filling the house with hearty fragrance, always with NPR or PBS in the background. This time of year — if we were lucky and the mood struck her — the kitchen aromas might include a nod to her New England upbringing with the perfect autumnal pairing of apple sauce and gingerbread.

Warmth, good smells, a backdrop of simmering sounds, the front hall had a bit of the ambience of a coffee shop: solitude, but not too much solitude; quiet, but not too much quiet; good energy, but not frenetic.

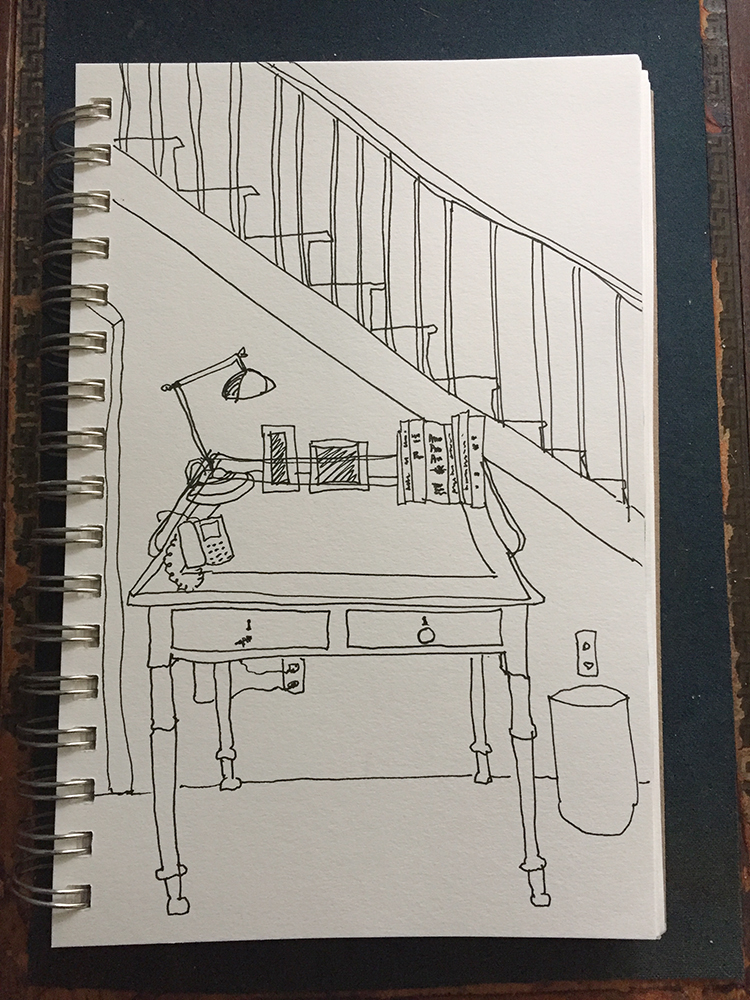

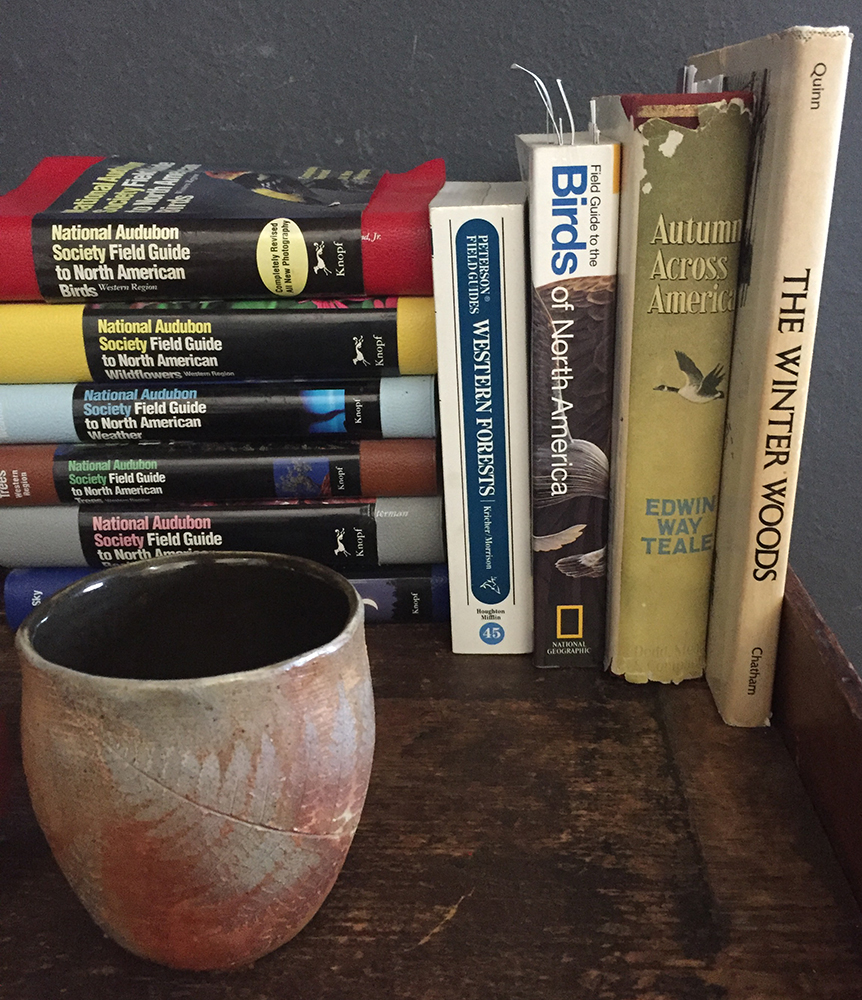

I worked most school days at the front hall table — some might call it a desk, with its two drawers — which sat beside the stairs, across from the heavy front door. The table hailed from the 19th century and was dinged and scratched with history. Its couple of drawers were crammed with phone books (remember those?), old PTA rosters, county info, pads of ruled yellow paper, and misfit pens and pencils. On its surface sat a phone, and next to that a reading lamp as well as a small miscellany of “nature books.” These books were of absolutely zero interest to me. I don’t remember ever cracking them open, though my parents might occasionally reach for the Peterson’s guide if an unusual bird showed up at the dining room window feeder. To me the books on the front hall table were nothing more than hallway decor.

Memory sketch of the front hall table in my childhood home.

Note the left drawer pull is missing; in its stead is an irremovable rusty screw, (wrapped in tape to prevent injury).

Years later when my parents made the tough decision to downsize and move out of my childhood home, a few hundred books made it to their new apartment, while hundreds more were donated to the local library. I brought back boxes of books to my New Mexico home, but the small collection of outdated nature books on the front hall table were not among them.

But the front hall table was! and it now sits in my own “hall” at the intersection of my kitchen, living room, bathroom and studio. Frequently the site of writing and watercolor explorations, the surface is once again cluttered with my “homework.” The drawers once again contain the accoutrements of communication: pens and pencils, assorted papers and envelopes, and town and county info. Here is where I often work on my weekly TuesdayDawnings and — as now — the occasional blog post.

One autumn day last year as I sat here at the hall table crafting an October edition of TuesdayDawnings and researching autumn verses, I chanced upon a beautiful statement:

Our minds, as well as our bodies, have need of the out-of-doors. Our spirits, too, need simple things, elemental things, the sun and the wind and the rain, moonlight and starlight, sunrise and mist and mossy forest trails, the perfumes of dawn and the smell of fresh-turned earth and the ancient music of wind among the trees.

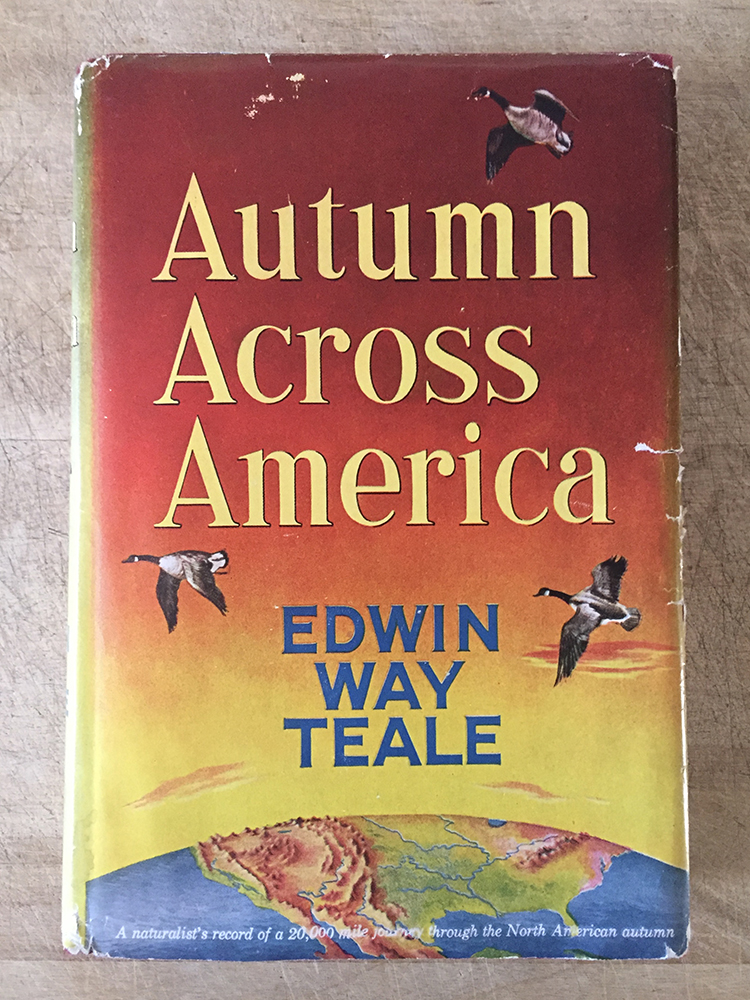

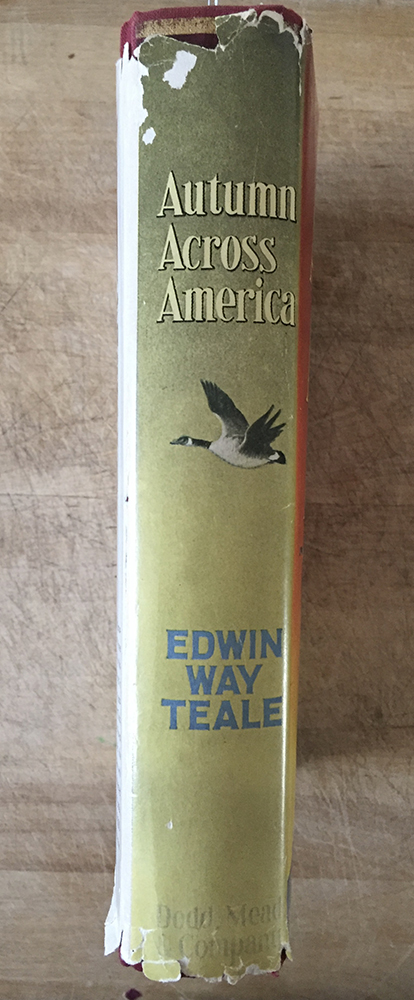

The author of those words is one Edwin Way Teale, a writer unknown to me although his name seemed vaguely familiar. It seemed the quote had been excerpted from a 1956 book of his titled Autumn Across America.

Intrigued by the appealing title, I decided to look up the book, never expecting that doing so would suddenly catapult me to being 17 again sitting at the front hall table poring over my homework with sounds of my mother emanating from the kitchen.

For the book cover of Autumn Across America was instantly familiar to me, the recognition so immediate and palpable that I it caught my breath: it was one of the books that had sat for some 40 years in the little tabletop library of our front hall.

How many times all those years ago had I looked up with desperation from the cryptic equations in my algebra homework and stared hopelessly at the golden spine of my parents’ copy of Autumn Across America? All those years ago it had kept me company most every school night as I grinded over my homework. Though I’d never read it — never paid it any mind at all — its cover now, 35 years later, seemed to smile at me from my computer screen as though it were an old friend.

I dove into a search for used books — and in a click I bought it.

Autumn 2019 was mostly past when my new old copy of Autumn Across America finally arrived, by which time my attention had turned to the poetry and expressions of winter. So I put aside Teale’s book as something to savor the following fall . . . 2020.

And so here we are, and savoring it, I am! Take this vivid passage from his October travels across Utah:

As it ran east our road paralleled the 125-mile chain of the Uinta Mountains, the only range in the United States that runs east and west. It carried us through canyons, pink-soiled and red-rocked or gray of soil and rock, sometimes with a silver stream of thistledown riding through on the wind. It crossed dry creek beds and rivers of stones. Magpies alighted treetops beside the road, balancing themselves with long tails bobbing up and down like pumphandles. More than once we passed weathered log cabins with sod roofs, some with tumbleweeds rooted in the roof soil. One that combined the old and the new was wired for electricity. Most stood in the shade of cottonwoods, the trees whose scraped inner pulp once provided the hard-pressed pioneers with a confection called “cottonwood ice cream.” Red foliage once more lay behind us. But aspen gold, pure, brilliant, shining, was scattered all around us. It covered the steeps, flowed down the declivities, massed along the creek banks. Then the gold, too, dropped behind us and we were among silvery sage brush and juniper forests so darkly green the trees looked black along the mountain sides.

Isn’t that luscious?

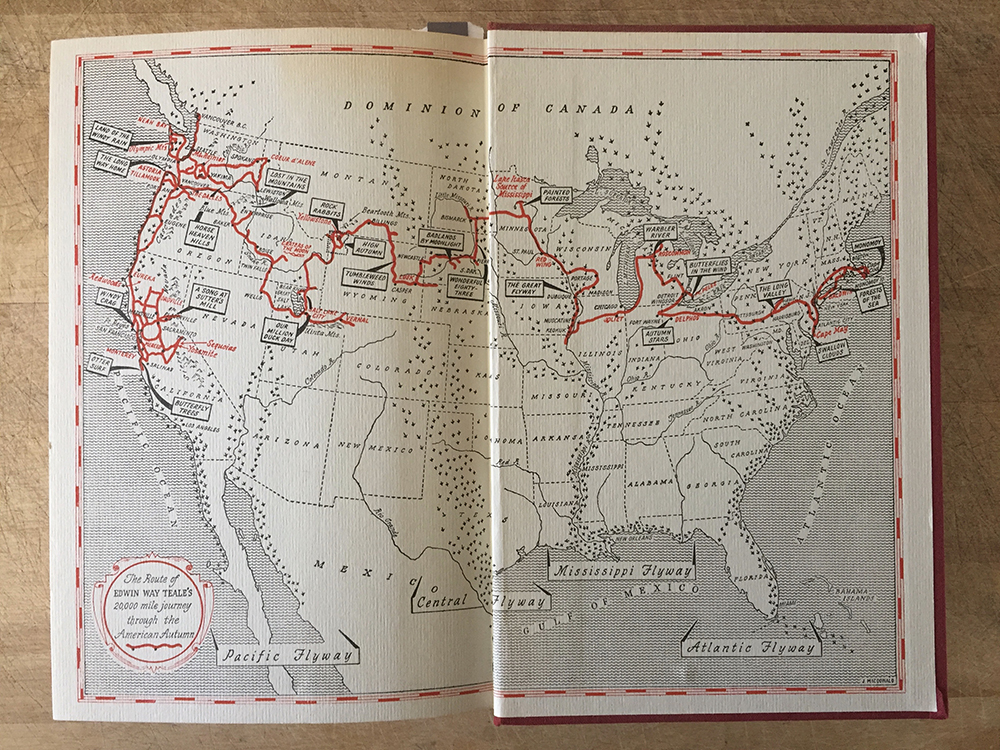

Teale was a naturalist. (In fact, at the age of nine he declared himself so[!]) In college he majored in English and went on to write for many years for Popular Science. Eventually he ventured out on his own to become freelance writer and photographer. In 1945, in part to deal with the grief of the death of their son killed in WWII, Teale and his wife Nellie set out on a road trip to explore the eastern American landscape. That proved such good medicine, that in 1947 they set out again covering some 17,000 miles in their Buick as they wove across the United States.

Teale chronicled their journey in a set of four books: North With the Spring, Journey into Summer, Autumn Across America, and Wandering Through Winter. Reading through a list of his awards and recognition (a Pulitzer among them), it’s clear Teale was well regarded in 20th century literary, scientific and conservation circles.

One of the things that strikes me so about Autumn Across America is Teale’s reverence — his rapture — for the outdoors. His writing is elegant and masterful leaving me in awe imagining what our American landscape looked like in the late 1940s. Reading his descriptions fills me with delight, but also with a wisp of wistful longing, as I imagine what little urban sprawl there was back before malls and condos, fast food joints and big box stores. How much brighter and more dazzling the night sky was. How free from plastic our roadsides and oceans were.

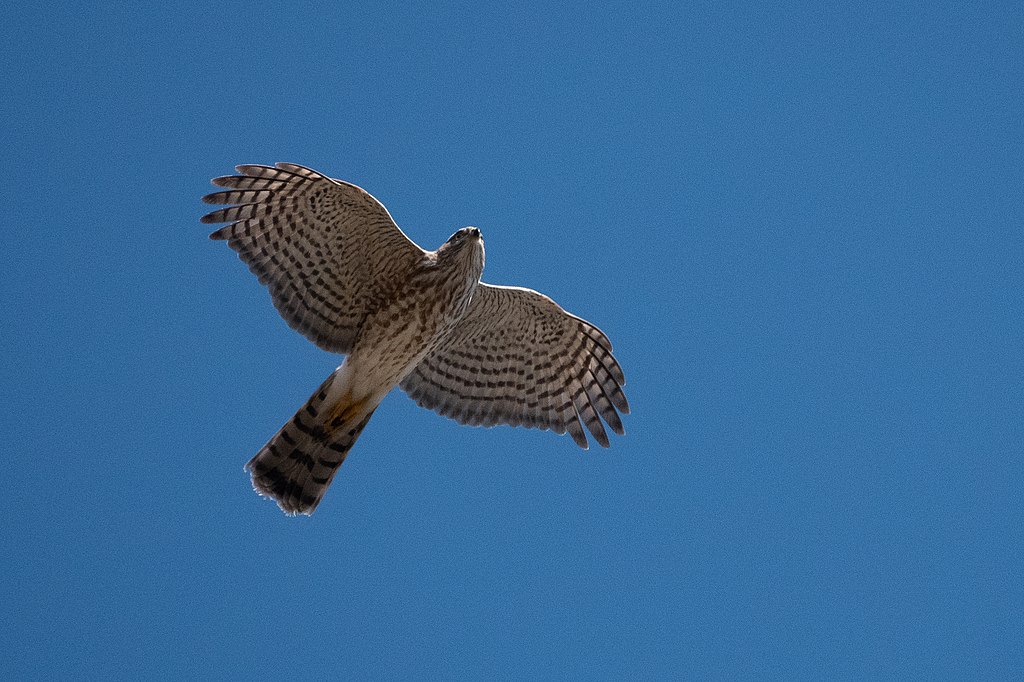

It goes without saying that there was plenty back then not to admire about the era. And as far as nature and the landscape goes, it’s hard for me to imagine a time when killing eagles and hawks was legal, but of course it was back then. Not until the Migratory Bird Act [MBA] was expanded in 1972 to protect raptors would the senseless killing of these magnificent beings come to an end. I wouldn’t be surprised if Teale’s book had a direct impact on those decision makers who expanded the MBA, inspiring them to pay mind — to notice — more of the natural word around them and take steps to protect it.

Teale, writing about Point Pelee near Detroit:

Charles Darwin, when he reached the illimitable pampas of Argentina during the voyage of the Beagle, noted that the average man rarely looks more than 15° above the horizon. The events of the sky above him occur, in the main, without his being aware of them.…

We, that morning, commenced to “pay mind“ to what was overhead when the shadows of hawks, one after the other, drifted along the sand…. The flight of the sharpshins had begun.

During September—with the migration waves reaching their peak in the middle of the month—these hawks pour down from hundreds of thousands of square miles to the north and pile up near the tip of this nine-mile arrowhead of sand. When in 1882 W.E. Saunders, an ornithologist of London, Ontario, first reported the autumn hawk flight at Point Pelee, he was hardly believed. The number of migrants shot there—in days when the hostility toward the swift accipiters was untempered by an understanding of their role in the balance of nature—gives an indication of the extent of this annual movement. One farmer sat in his front yard and shot 56 sharpshins without getting out of his chair. In 30 minutes, on a September day about the turn of the century, P.A.Taverner and B.H. Swales counted 113 sharpshins passing over the tip of the jumping-off place on the northern shore of the lake. Such flights first brought scientists to the area.

Sometimes the hawks we saw came low over the trees, bursting out upon us suddenly. At other times they soared down the point so far overhead they were only sparrow-sized in the sky. The lower migrants circled uncertainly when they reached the spit of sand with the edging of slaty-blue waves tinged with yellow from the mud of the shallow bottom. They mounted in an ascending spiral, beating their wings and gliding, then beating their wings and gliding again. High above us they straightened out at last and headed away across the water. Watching the “blue darters” thus, with hawk after hawk passing by, we noticed how endlessly varied in shading they were. Some appeared extremely light, others abnormally dark. How many hawks we saw that day I do not know. But hour after hour the parade continued…..

On this sunny September morning, under the migrating sharpshins another migration was taking place. It was there, in retrospect, the most dramatic event of the day. Whenever we think of Point Pelee we will always think of butterflies in the wind….

A sharp-shinnned hawk. Photo by Bettina Arrigoni

Last autumn when I was visiting my New Hampshire aunt** she welcomed me with a small dish of warm apple sauce and molasses cookies. Much like her sister, applesauce and ginger and molasses run in her blood.

When I went to pull a couple of mugs out of the cabinet for our tea, I asked her which of the assortment of motley mugs she’d like to use.

.

“I like the old things,” she said, gesturing to a mug that was at least half as old as she.

As I’m recalling that, I’m typing these words on the latest whiz-bang 21st-century tablet. I’m listening to a full orchestra without being in a theater and without a phonograph or radio, yet which is streaming to me seemingly magically.

Yet I’m doing all this while sitting at this banged up 19th century table with a splayed open yellowing old book written when my parents were but newlyweds. A book which, only in middle age have I come to appreciate, yet one which, though I was oblivious to it at the time, had kept me in good company more than three decades ago in my youth.

I’m sitting here in my little hallway working on my midlife “homework.” And though I can no longer hear the sounds of my mother cooking, her fragrance radiates warmly from my own kitchen as applesauce bubbles on the stove top and gingerbread rises in the oven.

And I realize that, much like my aunt, I like the old things, too.

And if I’m lucky and pay mind to the sky more than 15° above the horizon later today, maybe — just maybe — I’ll be blessed with seeing a hawk as autumn moves across America.

** My mother’s sister, who, a few weeks ago, turned 91 — and who, TWICE this summer, with a tennis racket and her still fierce serving arm, killed a bat that was loose in the house.

Moosehead Gingerbread

MY FAVORITE

(from The Fannie Farmer Baking Book by Marion Cunningham)

A firm, dense, dark and pungent gingerbread from Maine, very lively with mustard and pepper. Serve with applesauce, vanilla ice cream, or whipped cream.

Makes one 8-inch square cake

2 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 1/2 teaspoon powdered ginger

1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

1/2 teaspoon dry mustard

1/2 teaspoon ground black pepper

8 tablespoons (i stick or 1/2 cup) butter *

1/2 dark brown sugar

2 eggs

1 cup molasses

1 cup boiling water

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees. Grease and flour an 8-inch square pan.

Combine the flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, mustard and ground black pepper, and sift them together onto a piece of waxed paper. Set aside.

Put the butter and brown sugar in a mixing bowl and beat until smooth and well blended. Add eggs and beat well, then beat in the molasses.

Add the boiling water and the combined dry ingredients and beat until the batter is smooth.

Pour into the prepared pan and bake for 35 to 45 minutes, or until a toothpick or broom straw inserted in the center of the cake comes out clean. Remove from the oven and let cool in the pan for 5 minutes, then onto a rack. Serve warm or at room temperature.

*I use Myoko’s vegan butter, which, by the way, is superb.

Wilson Applesauce**

(My grandfather’s recipe, as dictated to me by my sainted mother)

1) Put a kettle of water on to boil

2) Quarter 4lbs of apples (my mother always used McIntosh)

— remove indentation at each end (No stems allowed!)

— leave core intact; remove rotten spots

3) shake a few shakes of salt over apples in a big pot

4) Pour boiling water @ 2/3 to 3/4 the way up the apples.

5) Dump 1 cup sugar over apples; don’t stir sugar in right away (or else it will settle on the bottom and burn)

6) Heat on moderately high heat to boiling. Boil until apples are soft and mushy (at least 1/2 hour)

7) Put through food mill.

8) Yummy!

**Or, as I titled it decades ago on y recipe index card: Sweetest Gramps’ Yankee Soul Sauce

(Wilson is my mother’s maiden name)

Thank you for being here and reading my musings. If you enjoy my posts I invite you to subscribe to this, my blog so you catch all my occasional musings. And by all means, if you know others who might enjoy these writings, please feel free to share this post with them.

Meanwhile, find more of my stories, insights and art here on my website, www.taosdawn.com. Peruse and shop for my art here. And please consider joining me for TuesdayDawnings, my weekly deep breath of uplift, insight, contemplation & creativity.

Stay safe. Be kind.

~ Dawn Chandler

Santa Fe , New Mexico

Photo of Dawn by Sylvie Vidrine